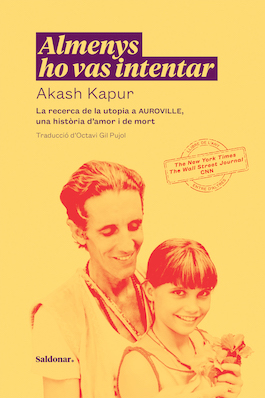

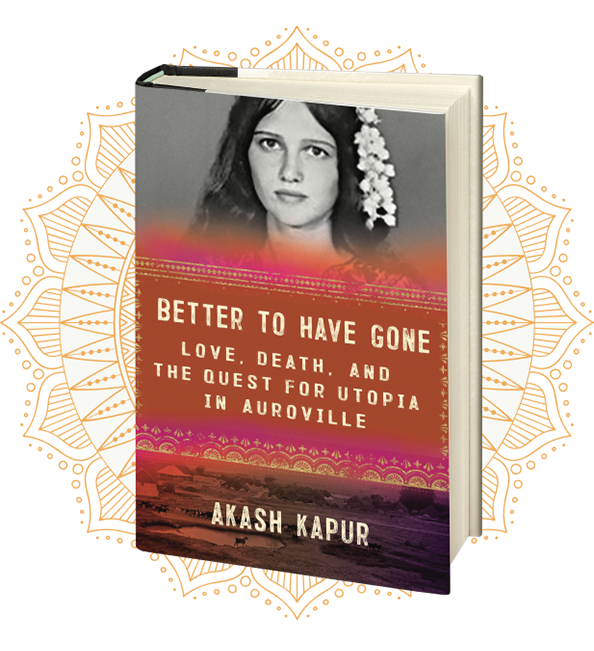

Better To Have Gone

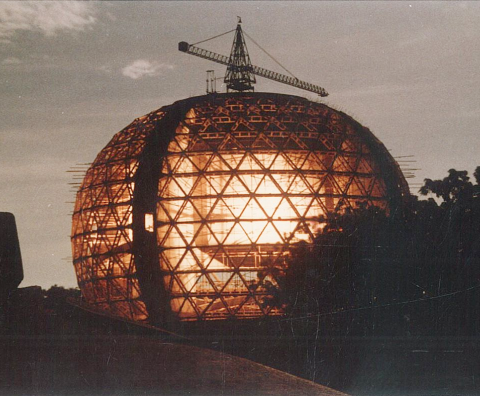

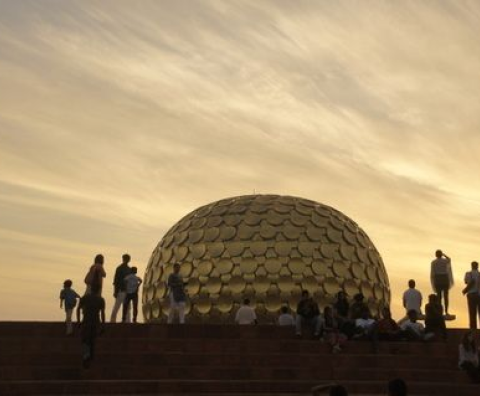

A spellbinding story of love, faith, the search for utopia – and the often devastating consequences of idealism.

- Named a book of the year by the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, CNN, New Statesman, Airmail, Scribd, Open magazine, and more. Shortlisted for the Tata LitLive Prize, longlisted for the Chautauqua Prize. Recipient of a Whiting Grant.

- “Haunting, heartbreaking … deeply researched and lucidly told, with an almost painful emotional honesty.” —Amy Waldman, New York Times Book Review (cover)

- “Extraordinary… a riveting account of human aspiration.” — The Boston Globe

- “Suspensefully structured, I consumed it with a febrile intensity” — New York Times

- “Beautiful… I read Kapur’s book with my heart in my mouth.” — Aatish Taseer, Airmail

- “Riveting… Kapur is a terrific storyteller.” — San Francisco Chronicle

- “Haunting, harrowing, moving.” — Nilanjana Roy, Financial Times

- “Propulsive … Expect the unexpected in this riveting story.” — Publishers Weekly

- “Beautifully written and structured. A nonfiction classic.” — William Dalrymple

As Featured In:

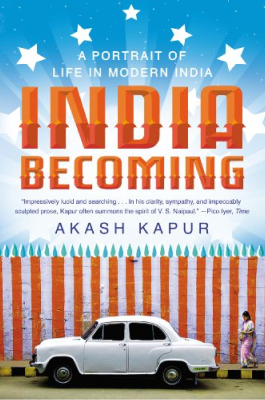

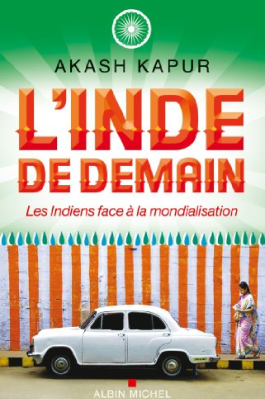

Other Books

A Better World

Selected Articles

Governing the Internet

The New Yorker: Will the Internet harden into an oligarchic playground, or will it become the tamer (and perhaps less innovative) place envisioned by European regulators, something akin to a digital public utility? Will large sections of it eventually bend to the power of tyrants and illiberal populists? Or will the more consequential influence be the model that India is pioneering, a walled garden in which private enterprise is allowed to flourish, but within confines established by the state?

The Return of the Utopians

The New Yorker: Contradiction and hypocrisy have always hovered over the utopian project, shadowing its promise of a better world with the sordid realities of human nature. Plato, in the Republic, perhaps the earliest utopian text, outlined a form of eugenics that would have been right at home in the Third Reich—which was itself a form of utopia, as were the Gulag of Soviet Communism, the killing fields of Pol Pot’s Cambodia, and, more recently, the blood-and-sand caliphate of isis. “There is a tyranny in the womb of every utopia,” the French economist and futurist Bertrand de Jouvenel wrote.

Rising Digital Nationalism

The Wall Street Journal, cover story Week in Review: The internet was never just a technology or an engine of globalization. It was, at its core, an idea. Like classical liberalism, the internet may also be a good idea in urgent need of updating. Much as the individualism and freedom of classical liberalism have been distorted into the inequalities and ethical transgressions of modern capitalism, so the internet’s culture of “permissionless innovation” has been abused, transformed into the centralized, controlled network of today.

Top of the world

The New Yorker: Cartography is a form of control. “The Great Arc,” John Keay’s account of the surveying operation, argues that the undertaking was both a scientific triumph and an exercise in imperial authority. The Great Survey heralded a golden age of Himalayan exploration and exploitation, in which young European men, monocles firmly in place and teakettles securely lashed to their porters’ sacks, set out in the explorer-conqueror mold of Christopher Columbus and Captain Cook. The mountains became stages for mystical self-discovery and Nietzschean improvement.

Is a Basic Income Utopian?

The Financial TimesThe contribution of utopian thinking is rarely in its particulars; blueprints for change have a way of collapsing in the face of human complexity (or, worse, turning into totalitarian nightmares). The real value of utopian thought is that it forces us to confront the present, and to at least acknowledge the need for a very different future.

A Third Way for the Third World

The Atlantic Last year, shortly after he was awarded the Nobel Prize for economics, Amartya Sen returned to his native India for a visit. One December morning, just outside Calcutta, at Santiniketan, the school where Sen had studied as a child, he was made to climb a dais and sit on a makeshift throne. News reports say that he looked tired, but he found the energy to address the assembled crowd. He reminisced about his childhood, and spoke of the influence exerted on his work by the school’s founder — Rabindranath Tagore, who in 1913 became the first Asian Nobel laureate when he won the prize for literature, and who, as Sen’s teacher, named him Amartya (Bengali for “immortal”).